Moo Deng, the baby hippo internet sensation, and the girl who was gored by a rutting stag in a London deer park highlight our sometimes-baffling behaviour around wild animals.

The Thai zoo where Moo Deng (bouncy pig), a pygmy hippopotamus, was born to great fanfare on social media, has restricted visitor numbers and appealed for restraint after people started throwing heavy objects at the hippo to get a squeal for their Tik Tok videos.

In London’s Bushy Park, a girl was injured when her parents took her too close to two fighting stags who use their massive antlers as potentially lethal weapons in their autumn rutting ritual fighting off love rivals.

Stupid?

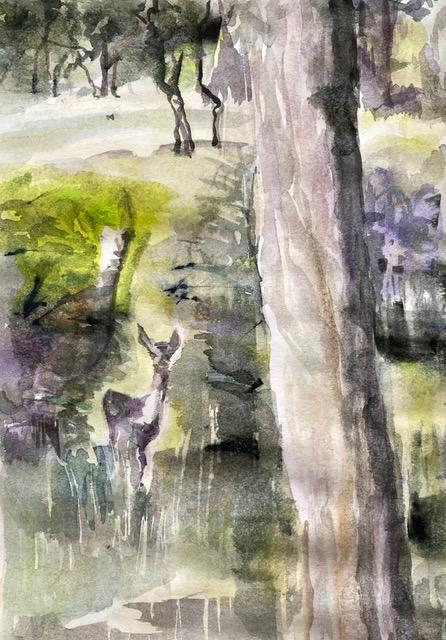

Are the actions of the people involved — mainly urbanites — stupid, or understandable? I’d say both. I’ve realised this while working as a volunteer ranger in Richmond Park, a 2,500-acre nature reserve in west London. Here, over 600 deer live wild throughout the year continuing their cycle of mating (and rutting) in the autumn, and birthing in the spring. At these times the deer can be especially dangerous to people and dogs who get too close.

No matter how many signs to keep at least 50 metres away and not to feed, many visitors will insist on getting as close as possible to the deer. Some attempt to feed the animals, while others have been seen trying to put their children on the deer for group selfies. And despite the well-documented erratic behaviour of dogs near deer, some owners refuse appeals to leash their pets, insisting that their pooch would never chase the animals.

People often “rescue” baby deer believing they have been abandoned by their mothers who leave infants in the long grass to go elsewhere to graze, returning to nurse their offspring. Touching or stroking the fawns (or calves) can be fatal because the mothers can reject their offspring if they carry human scent.

Baffling

These examples of human behaviour are indeed baffling, but only if you know something of deer behaviour. If you don’t (and why should you?) then it’s understandable. These beautiful creatures (there are six species in the UK, many roaming free) are for many people strongly associated with Disney’s Bambi. Why would Bambi object to a cute child on her back?

Given that our experience of wild animals derives mainly from watching wildlife programmes, we can be forgiven for getting a distorted view of their behaviours. It’s perfectly understandable that we see the fighting stags as somehow outside our immediate environment, as if on a screen. Why would they attack me or my child? We’re only watching.

Another baffling attitude is resistance to deer culling in the UK and USA. In states like Maine, Connecticut and New York, wild deer numbers have ballooned with hungry herds roaming through neighbourhoods destroying gardens and colliding with cars. But many highly-vocal locals argue against culling which they see as cruel. The consequence is that the animals are malnourished, weak and sick. Cruel indeed.

Culls

The Royal Parks, of which Richmond and Bushy are part, carry out annual culls to keep the deer numbers in balance with available food. This is not a secret but there is a reluctance to talk about it because of a noisy lobby against culling. The naysayers advocate chemical birth control, which the park managers say is impractical and ineffective.

We also have a strong urge to feed wild animals, probably because, as in “rescuing” baby bambis, it appeals to our nurturing instincts. For example, feeding ducks with stale bread is part of a British family outing, despite appeals not to because bread can harm the birds and pollute water courses. Ending the practice is made more difficult by mixed messages from animal charities. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) encourages feeding with bird food but admits that some birds depend on the bread thrown to them and would suffer if it was withdrawn. On the other hand, the Royal Parks bans the feeding of all animals in its parks but does little to police its diktat.

Wild

Volunteer rangers have no powers. We speak to bird feeders, explain the harm that bread can cause to wild birds and ecosystems, but we cannot stop the practice. Given that many people, especially the lonely, gain tremendous pleasure from interacting with the animals they feed makes it easy to walk on and ignore the transgression.

Human behaviour towards animals can indeed be baffling, but surely, we can be excused for not knowing better. Unless our parents were knowledgeable naturalists and taught us nature’s ways, we remain ignorant of the consequences of our often-well-intentioned actions.

It is all part of our contradictory attitude to animals: some we keep, kill and eat; others we kiss and encourage to sleep in our beds.